Reducing Lead Times in High-Volume Manufacturing: Strategies and Case Studies

High-volume manufacturers often define lead time as the total elapsed time from a customer order until product delivery. This spans all value-adding activities (processing, inspection) and waiting times (queues, transit) in the production and supply chain. Lead time is critical: shorter lead times mean greater agility, less inventory, and higher customer satisfaction. For example, Toyota’s production philosophy explicitly aims to “eliminate waste and shorten lead times” so vehicles reach customers faster at lower cost.

Conversely, long lead times force large safety stocks, inflate work‐in‐process (WIP), and delay revenue, as excessive waiting erodes productivity and customer loyalty.

Root Causes of Long Lead Times

Long lead times in high-volume plants typically stem from multiple interrelated issues:

- Supply-chain bottlenecks and variability. Global sourcing and long shipping distances introduce delays and uncertainty. For example, electronic part lead times have soared (raw material delivery times rose from ~65 to 81 days in recent years), forcing manufacturers to carry extra inventory. Single-source or distant suppliers (e.g. overseas semiconductor plants) can dramatically lengthen supply lead time. Supplier-side issues – equipment breakdowns, material shortages or regulatory holds – can cascade into major delays. Poor forecasting can worsen this: inaccurate demand plans often result in reliance on slower suppliers or expedited shipping, stretching lead times.

- Inefficient planning and scheduling. When production planning is done manually or with limited visibility (spreadsheets, siloed departments), resources are misallocated and bottlenecks form. One electronics contract manufacturer noted that spreadsheet-based scheduling led to “frequent delivery delays” and excess inventory, because planners had no real-time view of capacity. Late or uncertain material arrivals then throw off the entire schedule: “Late material deliveries throw off the entire sequence, resulting in rush orders, overtime, and equipment downtime while waiting for missing parts”. Inflexible scheduling (ignoring machine capacities or not reacting to delays) creates chronic waiting between operations, inflating lead time and WIP levels.

- Long changeovers and batch processes. Large batch sizes and lengthy setup times mean parts may wait for hours or days before the next operation. In many plants, queue (waiting) time dominates total lead time: parts sit idle between processes far longer than they spend on machines. Every extended changeover or excessive batch (e.g. running 1000 units at once) inserts non-value-added time into the lead time. Traditional “push” scheduling further compounds this by often building before orders arrive, causing inventory to sit and lengthen overall cycles.

- Equipment downtime and maintenance issues. Unplanned machine failures or slowdowns directly halt production, causing work to accumulate in queues. Proactive maintenance can mitigate this, but without it, any machine stoppage multiplies lead time for all following processes.

- Quality problems and rework. Scrap and rework send parts back into the production flow, effectively multiplying lead time. Poor first-pass yield forces repeated processing steps (each with its own cycle time and waiting), delaying final shipments. In high-volume settings even a small defect rate can cumulatively add significant lead time and waste.

- Non-value-added administrative delays. Excessive inspections, paperwork, or approval steps add overhead. Handoffs between departments or plants (e.g. from production to shipping) often incur fixed delays. While harder to quantify, these steps can introduce hours or days of waiting. Optimizing shop-floor processes (via Value Stream Mapping, for example) often reveals that queue and move times dwarf processing time in typical lead times.

In summary, lead-time drivers include everything from external supply-chain volatility and logistics to internal scheduling, changeovers, and quality issues. High-volume plants must identify which of these “time traps” dominates their flow. Techniques like time studies and value-stream mapping can pinpoint the biggest delays.

Click HERE for Industrial Automation, Manufacturing Operations, ISO Management Systems (ISO 9001, 45001, 14001, 50001, 22000, Integrated Management Systems etc.), Process Safety (HAZOP Study, LOPA, QRA, HIRA, SIS), Quality Management, Engineering, , Project Management, Lean Six Sigma & Process Improvement Self-paced Training Courses

Strategies to Reduce Lead Times

Reducing lead times requires a holistic approach. Major strategies include:

- Lean and Continuous Improvement. Lean manufacturing focuses on eliminating waste (muda) in flow. Techniques include Value Stream Mapping to identify and remove delays, Single-Minute Exchange of Die (SMED) to shorten changeovers, and systematic 5S workplace organization to eliminate search/motion waste. Just-In-Time production and Kanban pull systems ensure parts are produced only as needed, avoiding buildup of inventory. Visual management (dashboards, andon boards) makes bottlenecks immediately visible so teams can react. For example, Toyota’s Production System (TPS) strives to “make only what is needed, when it is needed”, thereby collapsing lead times. Across industries, lean projects routinely cut lead time by streamlining each step: in one case study, implementing lean (VSM, kaizen, better flow) slashed a spare-parts delivery lead time from 8.3 weeks to just 2.5 days.

- Digital Planning and Analytics Tools. Modern software can dramatically improve planning accuracy and visibility. Integrating MES (Manufacturing Execution Systems) with ERP and planning tools provides real-time data on WIP, capacity and order status. Finite-capacity Advanced Planning & Scheduling (APS) engines use that data to sequence jobs optimally and auto-adjust schedules when delays occur. For example, Sumida (an electronics manufacturer) replaced spreadsheet scheduling with a digital APS (Siemens Opcenter) and saw lead times drop by 75% while on-time delivery rose 35%. Predictive analytics (machine learning models) can further forecast bottlenecks and demand. Ford, for instance, uses predictive supply-chain analytics to optimize orders and has improved delivery times by up to 75%. In practice, this means using tools that continuously recalc lead-time estimates and update production plans as conditions change. Integrating APS and MES with ERP (and even with AI-based demand forecasting) yields “accurate lead time estimation” and dynamic scheduling, minimizing idle time.

- Flexible Automation and Workforce. Deploying automation that can be quickly reconfigured increases responsiveness. For example, flexible robotic cells or collaborative robots (cobots) can switch between tasks or product variants faster than fixed lines, cutting changeover wait. Automation also reduces manual handling and its variability. Flexible manufacturing systems are explicitly credited with “decreased factory lead times” among other benefits. Similarly, cross-training labor and using modular equipment (quick-mold change fixtures, universal stations) allows a swift shift from one product to another with minimal downtime. Preventive maintenance (often enabled by IIoT sensors and predictive maintenance algorithms) keeps equipment online, avoiding breakdown delays. Overall, higher uptime and the ability to “retool on the fly” means production can respond to order changes without long delays.

- Supply Chain Optimization. Since external delays often dominate lead time, optimizing suppliers and logistics is vital. Companies should build stronger supplier partnerships, share forecasts (CPFR), and diversify sources to avoid single points of failure. For example, telling suppliers a realistic demand plan can incentivize them to expedite or hold inventory, effectively shortening replenishment lead time. Where possible, near-shoring or using multiple local vendors cuts transit delays: “good suppliers who live nearby usually deliver faster than distant ones”. Smaller, more frequent orders (vs. huge bulk orders) can also smooth flow: one supply-chain guide recommends placing smaller replenishment orders to reduce provisioning delays. In practice, techniques include safety-stock optimization (so inventories buffer only true uncertainty), vendor-managed inventory programs, and investing in visibility (GPS/IoT tracking of shipments) to react quickly to disruptions. Some firms even incentivize suppliers for on-time delivery or retain a mix of domestic and international sources to balance cost vs. speed.

- Quality and Process Control. Eliminating defects directly shortens lead time by removing rework. Implementing robust in-process quality checks, automation in inspection (vision systems, automated test) and poka-yoke error-proofing prevents slowdowns. Digital quality management systems (QMS) can rapidly detect drifts so corrections happen before bad parts accumulate. For example, Bosch reports its predictive-quality analytics reduced defects drastically, indirectly supporting shorter lead times by avoiding rework loops. In addition, standardizing processes (e.g. through SOPs, lightweight automation) reduces variation in cycle times, making scheduling more reliable.

By combining these strategies, manufacturers tackle lead time on multiple fronts: eliminating waste on the shop floor, improving planning precision, automating flexibly, and de‐risking the supply chain. Importantly, these methods reinforce one another (e.g. digital planning boosts lean execution; lean housekeeping enables more stable automation).

Click HERE for Industrial Automation, Manufacturing Operations, ISO Management Systems (ISO 9001, 45001, 14001, 50001, 22000, Integrated Management Systems etc.), Process Safety (HAZOP Study, LOPA, QRA, HIRA, SIS), Quality Management, Engineering, , Project Management, Lean Six Sigma & Process Improvement Self-paced Training Courses

Case Studies of Lead Time Reduction

Several real-world examples illustrate dramatic lead-time improvements through these methods:

- Lean Production (Automotive Spare Parts): An automotive OEM implemented lean methods (value-stream mapping, flow re-layout, Kanban pull, 5S, etc.) for dealer spare parts. After kaizen events and process redesign, the replacement-part lead time plunged from 8.3 weeks to 2.5 days. This massive cut was achieved by removing non-value steps (like excessive batching and unnecessary inspections) and by organizing the parts process for continuous flow.

- Digital MES Implementation (Industrial Machinery): Weir Minerals (mining pumps) rolled out a cloud-based MES across fabrication and assembly lines. Real-time shop-floor data enabled quicker decision-making and bottleneck relief. The result: some products saw lead-time cuts of 30% after the MES implementation. The plant also achieved 53% higher throughput and 37% less WIP by aligning production to actual demand and capacity.

- Advanced Planning System (Electronics EMS): Sumida Lehesten (an electronics EMS provider) faced complex scheduling challenges. By deploying Siemens Opcenter APS (tied into their ERP) with intelligent planning logic, planners gained a real-time model of capacity. This led to a 75% reduction in lead time and a 35% jump in on-time delivery. The APS allowed splitting orders by process step and dynamically prioritizing jobs, eliminating the old “one-batch-at-a-time” delays.

- Additive Manufacturing (Aerospace Retrofit): Airbus needed custom interior panels on tight retrofit schedules. Traditionally these would require custom tooling (with long lead times). Instead, Airbus printed the parts with industrial 3D printers. The result was “drastically faster time-to-market than conventional manufacturing”, since no mold-making was needed. In one example, a small batch of complex cabin panels that would normally take weeks in tooling were produced in days via additive manufacturing, saving both time and cost.

- Industry 4.0 Transformation (Packaging): Intertape Polymer Group (IPG) undertook a broad digital transformation (analytics, machine sensors, 3D printing for spare parts, etc.). In one striking outcome, they cut machine-spare lead times from weeks to a few hours. By printing critical spare components on-demand and using real-time machine-health analytics, IPG achieved 75% cost savings and nearly instantaneous replenishment of parts that used to take up to three months. This example shows how integrating lean culture with digital tools (AR training, cloud maintenance, IoT sensors) can eliminate traditional delays entirely.

These cases illustrate a common theme: whether through lean retooling, smart software, or new technologies, focused effort on lead time reduction yields outsized benefits (inventory reduction, cost savings and customer satisfaction).

Click HERE for Industrial Automation, Manufacturing Operations, ISO Management Systems (ISO 9001, 45001, 14001, 50001, 22000, Integrated Management Systems etc.), Process Safety (HAZOP Study, LOPA, QRA, HIRA, SIS), Quality Management, Engineering, , Project Management, Lean Six Sigma & Process Improvement Self-paced Training Courses

Metrics for Tracking Lead-Time Improvements

To guide improvement, manufacturers should track a variety of metrics, not just a single number. Key metrics include:

- Order-to-Delivery Lead Time: The full cycle time from customer order placement to shipment. This is often broken into components (e.g. procurement lead time, production lead time, shipping lead time). Monitoring these sub-metrics reveals where delays occur.

- Production (Manufacturing) Lead Time: Time from work-order release to finished goods. This can be further split into value-added processing time vs wait time. Value Stream Mapping often finds that >60% of manufacturing lead time is non-value-added wait. Tracking cycle times at each workstation (and variance) helps spot bottlenecks.

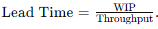

- Work-In-Process (WIP) Levels: WIP can be converted (via Little’s Law) into lead time:

.Thus, rising WIP or falling throughput indicates lead time will increase. Targeting lower WIP helps reduce lead time.

.Thus, rising WIP or falling throughput indicates lead time will increase. Targeting lower WIP helps reduce lead time. - Throughput / Cycle Time: Throughput (units/day) and average cycle time (time per unit at a station) reflect flow efficiency. Improving machine utilization and balance raises throughput, shortening lead time for a given batch size.

- On-Time Delivery (OTD) and Schedule Adherence: The percentage of orders fulfilled by the promised date. Often tracked daily or weekly, OTD indicates how well lead time commitments are being met. For example, Sumida improved OTD by 35% when lead times fell.

- Inventory Turns or Days of Supply: As lead time shrinks, fewer days of inventory are needed. Monitoring inventory turns (sales/average inventory) or days-on-hand signals lead time trends: slower turns imply longer lead times or excess buffering.

- Quality Metrics (Yield, Rejection Rate): Defect rates tie directly to lead time because rework loops add extra processing. First-Pass Yield on key processes and customer-return rates are indirect indicators that longer lead times may be hidden in poor quality.

- Value-Added Percentage: Lean metrics often compare value-added time to total lead time in a Value Stream Map. For instance, a map might show 90% wait vs 10% value-add. In one case, lean work increased value-added ratio from 66% to 90% of the lead time (reflecting that almost all waiting was removed). Tracking this shows how much of the lead time is genuine processing vs waiting.

Regularly reviewing these metrics at all levels (shop floor, management) is crucial. Small drifts (e.g. a few percent increase in material lead time) can signal upstream issues that need root-cause analysis. Dashboards that break down total lead time into segments (planning, queue, processing, shipping) help teams identify and prioritize improvements. Balanced metrics also ensure lead time reduction does not sacrifice quality or cost – for example, by setting targets for lead time alongside on-time delivery and defect rate.

By closely monitoring these KPIs, teams can quantify progress and quickly detect slippage. Continuous improvement then becomes data-driven: a weekly review might track whether a lean kaizen or new scheduling algorithm actually delivered the expected lead-time drop. Over time, such transparency helps sustain gains.

In conclusion, high-volume manufacturers can sharply cut lead times by attacking waste throughout the value stream, leveraging technology for visibility and agility, and tightly aligning the supply chain. The payoff is significant: faster time-to-market, lower inventory costs, and stronger competitiveness. The examples above show it is possible – but it requires measuring diligently, engaging people in lean habits, and using the right mix of people, process and digital tools.

Click HERE for Industrial Automation, Manufacturing Operations, ISO Management Systems (ISO 9001, 45001, 14001, 50001, 22000, Integrated Management Systems etc.), Process Safety (HAZOP Study, LOPA, QRA, HIRA, SIS), Quality Management, Engineering, , Project Management, Lean Six Sigma & Process Improvement Self-paced Training Courses

- Industrial Process Automation Training Course

- Advanced Digital Manufacturing & Product Design Technologies Training Courses

- Integrated Management Systems (IMS) Implementation Masterclass

- Integrated ISO Management Systems (IMS) Audit – Best Practices

- ISO 19011: Auditing Management Systems – Techniques & Best Practices

- ISO 9001 Quality Management Systems Lead Auditor

- ISO 14001 Environmental Management Systems Lead Auditor

- ISO 45001 Occupational Health & Safety Lead Auditor

- ISO 50001 Energy Management Systems Lead Auditor

- Food Safety Management Systems (FSMS) Implementation

- ISO 22000 Food Safety Management Systems Lead Auditor

- FSSC 22000 Lead Auditor (Food Safety)

- ISO/IEC 17025 Laboratory Management Systems (LMS) Certification

- Laboratory Management Systems (LMS) Essentials

- Lean Six Sigma Yellow Belt Certification Course

- Lean Six Sigma Green Belt Certification

- Lean Six Sigma Black Belt Certification

- Lean Manufacturing Certification Course

- Six Sigma for Manufacturing & Operational Efficiency

- Statistical Process Control (SPC) Training Course

- Measurement Systems Analysis (MSA) Training Course

- Strategic Supply Chain Management Training Course

- Operational Risk Management Training Course

- Quality Management Training Course

- Health, Safety and Environment (HSE) Training Course

- Advanced Digital Manufacturing & Product Design Technologies Training Courses

- Safety Instrumented System

- Hazards and Operability Study (HAZOP)

- Layer of Protection Analysis (LOPA)

- Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA)

- Process Safety Management (PSM)

- Industrial Process Safety